The classroom buzzed with vivacious debate.

“It needs to replicate.” “Consume energy.” “Be made of cells?” “Yes.” “No!”

It was the first day of my Caltech astrobiology course, and my students were already at each other’s throats, trying to settle a question that had tortured the minds of philosophers and scientists throughout the ages: What is life?

I thought it would be a logical opening activity. After all, we were embarking on a 10-week journey to investigate the science of life’s origins, life’s distribution, and the search for life elsewhere in the universe. So, first we had to decide: What is originating? What are we looking for? What are we, such that if we found something sufficiently like us, would we no longer be alone?

I began class by sharing some historical examples of the definition of life. Many ages ago, Aristotle said, “Life is something that grows, maintains itself, and reproduces.” In 1944, the physicist Erwin Schrödinger wrote, “Life is that which creates order and resists decaying to equilibrium.” And, just yesterday, the infinite wisdom of the Interwebz returned, “Life is a sexually transmitted, terminal disease.” All of these definitions had holes in them, which we poked at thoroughly before I set my students off, in small groups with big ideas, to formulate their own answers to this timeworn riddle.

“Should it be made of carbon?” “Able to move?” “Evolve!” “Darwinianly?” “Maybe.” “Are you sure?”

Once the groups had settled on their definitions—each its own constellation of criteria—we wrote them on the board and put them to the test. Do bacteria satisfy your definition? Excellent. Does your instructor? Phew. How about viruses? Hmmm. Self-replicating robots? Fascinating. What about fire, hurricanes, crystals, Internet memes?

Stars? Wow!

The thing I love most about teaching is that although I’m allegedly the distributor of knowledge, I’m constantly learning, too. Initially, I was surprised that stars satisfied most of my students’ definitions of life. This unexpected twist suggested two possibilities: Either my students were insane, or—far more likely—they were touching upon something profound. What could make stars seem alive? After all, they are not “life” by any conventional use of the word. We all agreed on that…yet, as some of my students argued:

Stars fuse hydrogen into heavier elements to keep themselves going (a form of nuclear metabolism, if you will). They also maintain a balance, or homeostasis, between gravity and pressure for millions to billions of years. And they even reproduce; through violent explosions at the ends of their lives, they recycle their “star stuff” back into the cosmos, sowing the nebular seeds for the next generation of stars.

My class made me realize that “lifeness” is not binary—it’s a spectrum. Phenomena across the universe and at all scales can appear life-like in different ways. Fire, for instance, transforms biotic matter and atmospheric oxygen into carbon dioxide and water—exactly as we humans do. Hurricanes, on the other hand, sustain complex spiral shapes over hundreds of kilometers so long as they are fed heat and moisture, just as life maintains its own order when provided the energy and materials to do so. Even non-material things, like Internet memes, can proliferate with abandon the same way that bacteria grow exponentially under ideal circumstances. All of these phenomena are similar to life, but clearly aren’t alive. Was there a precise (and concise) way to describe how and why?

In other words, did I have a better definition of life?

Alas, the class realized that their emperor wore no clothes. “No,” I said, sheepishly. “I, too, have no good definition of life.”

That would remain true…until I met Stuart Bartlett.

New stars coalesce from the ashes of dead ones in this star-forming region in the constellation Cygnus (The Swan), imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope. Credit: NASA/ESA.

Stuart Bartlett is the kind of scientist who builds electric skateboards in his office while his computer code compiles and the kind of person who views mountain biking trails as paths to enlightenment. He is one of the most open-minded academics I have ever encountered, with a hunger for new experiences steeped with a profound awe of the natural world.

Stuart’s intellectual journey wended its way through Southampton, England, Lausanne, Switzerland, and Tokyo, Japan, before arriving at his current abode in Pasadena, California. Just as his travels have made him a citizen of the world, it’s difficult to localize Stuart’s scientific soul within the rigid confines of a single academic department; his breadth of inquiry transcends traditional categorization. Stuart embraces interdisciplinarity on his quest to explain life not only as it is, but also as it could be.

It wasn’t long after his arrival at Caltech that Stuart and I realized that we had something in common: a growing sense of disillusionment with divisions in the community of scientists who study the origins of life. Everywhere we looked, the field was splintered into various camps, each preaching its own “one true explanation” for life’s emergence. At meetings, when facts and figures ran dry, some scientists supplemented their arguments with insults, intimidation tactics, or the occasional chair hurled across the room. Stuart’s and my most harrowing experiences with origins-of-life scientists resulted in our mentor, Professor Yuk L. Yung, calling the entire discipline a “holy war.”

The first step towards brokering peace, Stuart and I surmised, might be to offer a new, more expansive definition of life.

Dr. Stuart Bartlett. Credit: Nerissa Escanlar.

Stuart’s outside-the-box perspective helped him identify four key activities that every living system performs. His emphasis on processes resonated with my own reckoning that life was “a verb, not a noun.” In other words, what distinguishes life from non-life are the things that it does, not the material from which it is made. So, what are Stuart’s “four pillars” of life?

First, dissipation: employing useful forms of energy to do beneficial work. On the human scale, wind turbines, for example, convert kinetic energy into electricity. At the nanoscale, life uses a molecular turbine that runs not off of wind but a flow of protons. This turbine, called ATP synthase, converts that flow of protons into molecules of ATP, the so-called “energy currency of life.”

Second, autocatalysis: the idea that life begets more life, enabling the indefinite growth of some representative metric of the system under ideal circumstances. One observes this pillar in population growth, DNA replication, or in the way the products of biochemical reactions often include ingredients required to run those reactions again.

Third, homeostasis: the act of maintaining the correct internal conditions to thrive. For instance, if you step out into the brutal southern California summer, your body will fight to keep your internal temperature stable by sweating. Other processes regulate blood pressure, ion concentrations, acidity, etc.

Finally, learning: recording information about one’s environment and processing that information in a beneficial way. Life on Earth learns in myriad ways, from storing evolutionary memories in genetic polymers, like DNA and RNA, to storing lived experiences in neurological structures, like the brain.

The four pillars of lyfe. Credit: Cecilia Sanders.

Stuart and I began using the term “lyfe” to describe anything that might satisfy all of our criteria. Why a new term? Because the four pillars describe a class of systems that subsumes life as we know it. This way, we preserved the familiar meaning of the word “life”—it is the particular instance of lyfe observed on Earth.

In a recently published paper, Stuart and I make the case for the lyfe as an alternative paradigm for origins-of-life research. The standard approach to understanding the origin of life is to determine the origins of life’s modern-day “building blocks”—be it RNA, proteins, or lipid vesicles. However, Stuart and I encourage our fellow scientists to seek origin scenarios that result in lyfe’s four fundamental processes, rather than merely a proclivity for making specific molecules that we don’t really know were relevant to nascent life. This is important because it’s impossible to know exactly what happened during life’s onset on Earth. Perhaps the simplest system that achieved all four pillars looked nothing like life does today. In other words, perhaps it was lyfe.

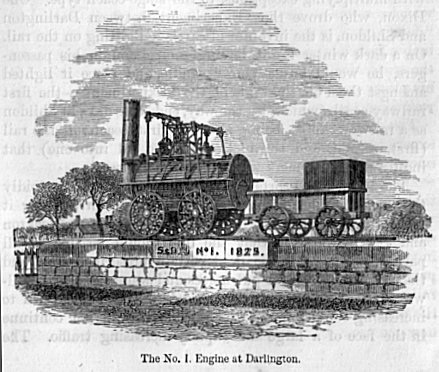

Think of modern life as the cutting edge of train technology: a Shinkansen, or bullet train. This beast is encased in carbon fiber, powered by superconducting magnets cooled with liquid helium, and guided by a computer. Consider how different this is from the train’s humble beginning: a locomotive made of wood and iron, powered by an inefficient steam engine, and controlled by a grimy human conductor. By examining a Shinkansen and knowing nothing else, could you determine what the earliest train looked like? That might be a tall task. But could you say what the earliest train did, at the most general level? Well, yes, pretty much the same thing it does now. While train materials have evolved greatly over time, the overall function of a train has remained the same.

Thus, in the search for life’s origins, as well as the search for life elsewhere, actions may speak louder than molecules.

Left: An early steam locomotive (credit: Samuel Smiles). Right: A modern Shinkansen (credit: Daylight9899).

Because the four pillars of lyfe are indifferent to the materials that constitute the system, they open the imagination to living systems that are radically different from familiar biology. While the concept of “life as we don’t know it” is not new (just ask any fan of Star Trek), the four pillars give us definitive criteria with which to address the lifelikeness of any extraterrestrial oddity. Traditional astrobiological vocabulary can be fuzzy on this matter. Take NASA’s definition of life, “a self-sustaining chemical system capable of Darwinian evolution.” Why should we disallow a mechanical being?

The hydrocarbon lakes and seas of Saturn’s moon Titan represent a prime location for the search for lyfe. If living entities exist in Titan’s frigid (94 kelvin, or –179 °C) environments, they would be constructed in a totally different way from life on Earth (where temperatures hover around 288 K, or 15 °C). Some authors have even suggested the possibility of non-cellular life on this exotic world—a truly novel form of lyfe, if it does indeed exist.

Stuart and I encourage the scientific pursuit of lyfe, both in the lab and among the stars, because these searches can lead us to a deeper understanding of what, how, and why we are. If we find that lyfe exists only in the form of life, that would suggest that the specific molecular components of life are uniquely capable of producing the living state.

However, if we find that lyfe is not limited to a specific composition, life as we know it would represent just one particular manifestation of the four pillars. Similarly, planet Earth would represent just one type of environment in a vast (perhaps infinite) expanse of possibilities that could host living systems. Should this be the case, lyfe might be lurking in places where we would never dream of looking for life.

Scientists use the term “emergent” to describe systems whose collective properties go beyond the sum of their parts. For example, the laws of fluid motion emerge in materials with wildly different microscopic properties. We may live in a universe where “lyfeness” is emergent, prolific, and diverse in form. Or we may live in a universe where life is a freak accident that just so happened to play out in our particular chemical soup.

We don’t yet know which universe we live in, but we hope it will be our generation that finds out.

Radar imagery from the Cassini spacecraft of the hydrocarbon lakes and seas of Titan's northern hemisphere. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASI/USGS.

One of the most beautiful things about the four pillars of lyfe is that they not only offer us a simple checklist for identifying living systems, they also help us place life within the context of other phenomena in the universe. Stuart and I also introduced the term “sublyfe” to designate systems that perform some—but not all—of the four pillars of lyfe. Such phenomena include fire, machine learning algorithms, and viruses.

Finally, I could put into words why stars passed many of my students’ tests for life. Stars do share several qualities with life—they are a form of sublyfe. Critically, however, stars do not learn. They do not record information about their surroundings in any way that promotes their own survival.

I now teach my astrobiology class at the University of Washington in Seattle. I begin the course exactly the same way: Aristotle, Shrödinger, the same stupid Interwebz joke. Then, I let my students develop their own answers in groups. When they’re done, we hold each group’s definition up to the jury of their peers. Unsurprisingly, stars pass a few of them.

As the period winds down, I close my first lecture more confidently than ever before. “I would never ask you to do something I couldn’t do myself,” I lie, recalling the Caltech class that called my bluff.

This time, however, it’s different.

“Stick around for the next 10 weeks, and I’ll share with you my own definition of lyfe.”